Craterhab Technology for Mars - Frequently Asked Questions

- M Akbar Hussain

- Jan 9

- 6 min read

For some time, I have been considering writing a section of Frequently Asked Questions for Craterhab Technology. But for me who has an internal perspective of our technologies, I found a certain bias if I tried to create a set of questions. Therefore I always welcome questions which help me understand the gaps between my explanation and a reader's or commentator's understanding.

Huzaifa Mustafa, a UET Taxila (Pakistan) graduate of the year 2024 has asked a few questions which are quite focused and relevant. So I decided to use his questions as FAQs and attempted to give concise answers which I hope clarify few concepts about the Craterhab and its related technologies for human habitation on Mars.

How can the fabric dome hold so much air pressure without ripping apart?

The amount of pressure maintained inside the Craterhab will be +0.15 to +0.3 bar (above ambient) for terrestrial applications, and +0.4 to +0.6 bar for space applications such as for the colonies on Mars, with a safety factor of 2.5x. This means these domes are designed to withhold at least +0.75 bar pressure on Earth and +1.5 bar on Mars.

The main shear forces on a dome are:

Hoop stress; the stretch force on any given section of the body of the dome, like that on the body of an inflated balloon, and

The vertical inflation force: This is the unbalanced vector of the inflation force in the upward direction, trying to lift the whole dome upwards. This force is tremendous. A 10m diameter dome with a pressure of +0.2 bar above ambient will be subject to over 600 tons of upward lift.

These stresses can be countered with

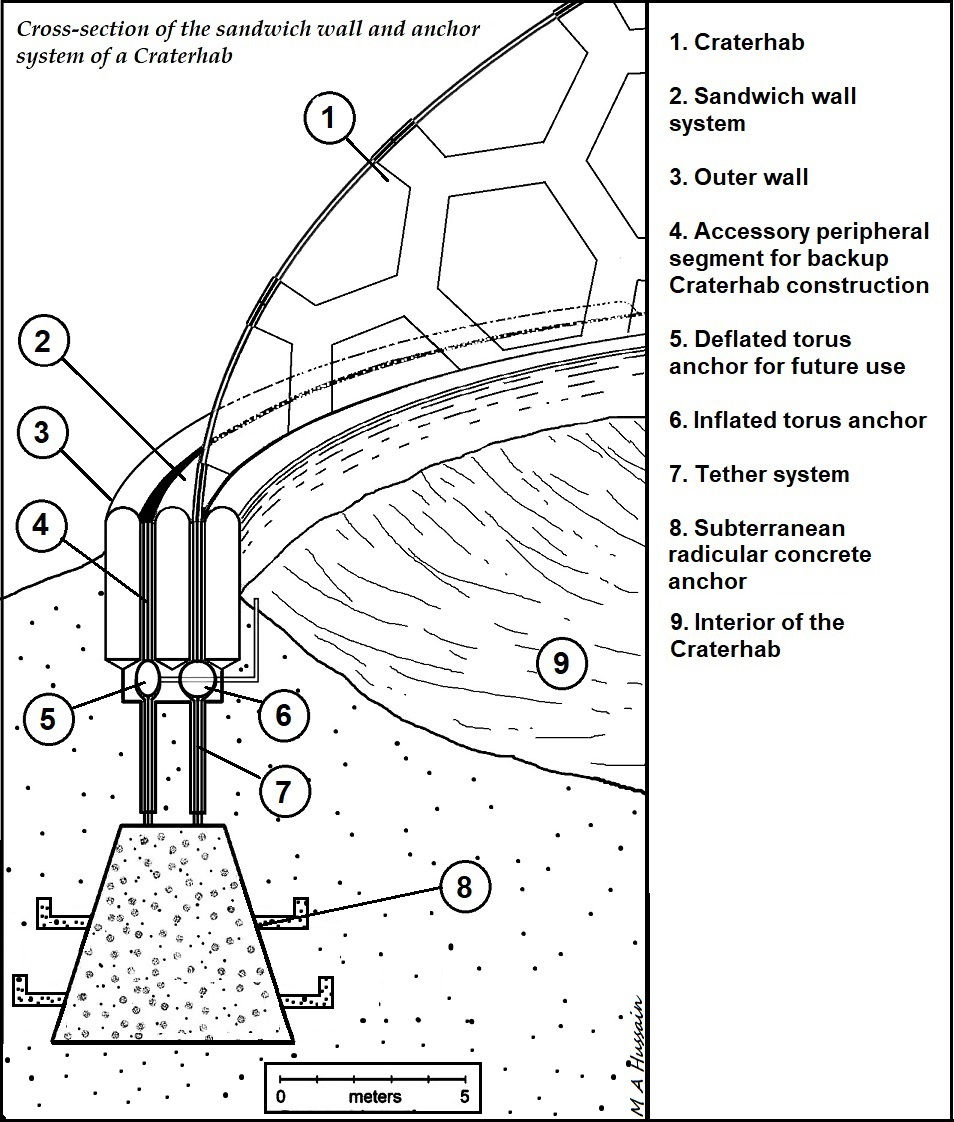

Choice of material: The dome is made up of the hexagonal skeletal frame of Dyneema (spectra) cables which is one of the highest tensile strength fabrics in industrial application. The thickness of the cables, and the number of hexagonal segments is carefully calculated to be able to withstand the hoop stress by a factor of at least 2.5x. The weaved laminate mesh inside the hexagons made up of Kevlar or other aramids will provide added strength. The dyneema skeletal frame will continue downwards through an underground sealing torus anchor as a tether system into a subsurface anchor system (concrete or helical anchors). The depth and size of the anchor system can be determined for the inflation force per individual anchor. The Dyneema tether system can be tens of cm in thickness, like mooring ropes for large ships, to be able to sustain the upward inflation forces.

Underground anchors. For smaller prototype and pilot domes, steel helical anchors may be sufficient. For larger domes, bigger and more permanent concrete anchors with radicular appendages for firmer hold may be required, Larger domes (100m+) diameter will have internal biradial cable network firmly attached to the underground anchors.

If the shear forces on the dome can be calculated accurately, the dome components parameters can be worked out. We have calculated material parameters for up to 500m diameter domes for Martian colonies, which can also be extrapolated as per the need.

Will the plastic material break down in the freezing cold and harsh sunlight of Mars?

Yes, it can. That is why, the exterior surface of the Craterhab will be covered in a thin layer of Polyimide or Kapton which is cheap and readily available, and protects material against the vacuum of space.

Where will the huge amount of electricity come from to run the radiation shield?

Our patented on-demand Active Integrated Radiation Shield (AIRS) is an essential part of our proposed surface habitats. Through the use of high temperature YBCO superconductors cooled to minus 180c will minimize the power consumption of the shield while producing a powerful non-ionizing electromagnetic shield to deflect high energy protons from cosmic rays (0.1 to 1 GeV) which otherwise would require several meters of regolith or water shielding creating structural and construction challenges.

This shield will require several tens to hundreds of kilowatts of power. Living and sustenance on Mars will require many times more power per capita in general as compared to that on Earth. Any settlement concept must cater for the power needs to sustain the liveability of the habitats such as temperature and pressure maintenance and protection from radiation, which is usually not required on Earth. With very limited solar flux, and no other viable local sources of power generation, nuclear fission will remain the mainstay of power generation. Unless fusion is made viable or other local exotic power sources are discovered and harnessed.

(Patent diagram of the Active Integrated Radiation Shield, or AIRS) Source: https://www.mareekh.com/post/craterhab-technology-an-engineering-overview-and-its-applications

Does melting frozen ground for energy really give more power than it takes to heat it up?

Our patented concept for power generation on Mars from exposure of subsurface ice to the thin Martian atmosphere in the form of superheated water from auxiliary power source utilizes rapid positive entropy generation in the cold sink of the thin Martian atmosphere. According to our observation, crystalline ice was formed from water percolating into the soil when the Martian atmosphere was thick, over 3 billion years ago. As Mars lost most of its atmosphere from Solar wind, the planet cooled down and all subsurface water froze into crystalline ice of low entropy. The thin Martian atmosphere can enable rapid generation of entropy far higher than can be achieved on Earth, if this ice is brought up to the surface as water and exposed to the Martian atmospheric conditions.

A cleverly designed system to bring up the subsurface ice to the surface as superheated water and utilizing low pressure of the Martian atmosphere to convert it into superheated steam, thus evading the steam conversion inside any of the energy input pathways, indeed seems to yield more energy than the input. This is partly due to the ability of vacuum-like conditions on the Martian surface allowing rapid achievement of very high entropy, utilizing the cold and thin Martian atmosphere as a very deep and steep heat sink. This is the core concept of our patented novel hybrid power generation on Mars - the Mareekh Process. Much of the extra energy obtained is in the form of latent heat, but due the cold conditions of the Martian surface, this latent heat can be utilized to warm up the interiors of the Craterhab, saving power which can be channelled to other purposes.

If a tiny space rock hits the balloon, will it pop and hurt the people inside?

Micrometeors are not a big issue on Mars as the thin Martian atmosphere is still sufficient enough to prevent sub millimeter meteors from reaching the ground by burning them off. The larger meteors do get to reach the Martian surface but they are not very common. The chances of small meteorites punching through the Craterhabs are slim, but never zero.

Our proprietary Smart Design feature of the Craterhab Technology is precisely crafted with this in mind. The fabric bilayer will have self-healing properties, In case of a small meteorite puncturing a hole a few millimeters across, the weaved laminate webbing structure of the dome will prevent the hole from spreading. Air leakage from the small home will slowly reduce the internal pressure of the Craterhab which will slightly shrink in size without any noticeable changes in the internal pressure. The slight shrinking of the dome will cause the multiple fabric layers of the dome to slightly slide past each other, sealing the hole temporarily, until definite repairs can be carried out.

How will they (martians ) clean the sticky Martian dust off the roof so sunlight can get in?

Martian regolith is very fine and sticky due to static charge. It is known to stick to the solar panels of the rovers. The advantage of using an inflatable fabric dome as habitat vs rigid glass, composite, or metal habitats, is that fabric domes have forgiveness and elasticity, resulting in very slight ripples travelling across their surface due to Martian winds. This can help keep the surface clean of the dust.

Have they actually built a small version of the radiation shield to prove it works?

Our patented Active Integrated Radiation Shield (AIRS) is specifically designed to deflect the majority of the high energy 0.1GeV to 1.0 GeV alpha particles in Galactic Cosmic Radiation (GCR) reaching the habitat. Earth’s surface does not receive any of this radiation due to its vast magnetosphere and a thick atmosphere. Creation of such particles will require a tremendous amount of power. Therefore this radiation shield cannot be tested on Earth.

How do they tie the dome down securely in loose sand and low gravity?

Mars has only 38% of the gravity as that on Earth. Flat regions of Mars are covered in several meters thick regolith, which is quite loose or less compact due to low gravity. Installing pressurized habitats on Mars anchored to the ground is a huge challenge.

Mars has millions of small Craters between 50m to 500m in diameter, or larger. The circular rims of these craters are composed of exposed bedrock which have much more compactness than the loose regolith of the flat surface. These compact rims provide an excellent interface to install underground anchors for the Craterhabs.

Comments